Hashimoto's Disease

On this page:

- What is Hashimoto’s disease?

- How common is Hashimoto’s disease?

- Who is more likely to develop Hashimoto’s disease?

- What are the complications of Hashimoto’s disease?

- What are the symptoms of Hashimoto’s disease?

- What causes Hashimoto’s disease?

- How do doctors diagnose Hashimoto’s disease?

- How do doctors treat Hashimoto’s disease?

- How does eating, diet, and nutrition affect Hashimoto’s disease?

- Clinical Trials for Hashimoto’s Disease

What is Hashimoto’s disease?

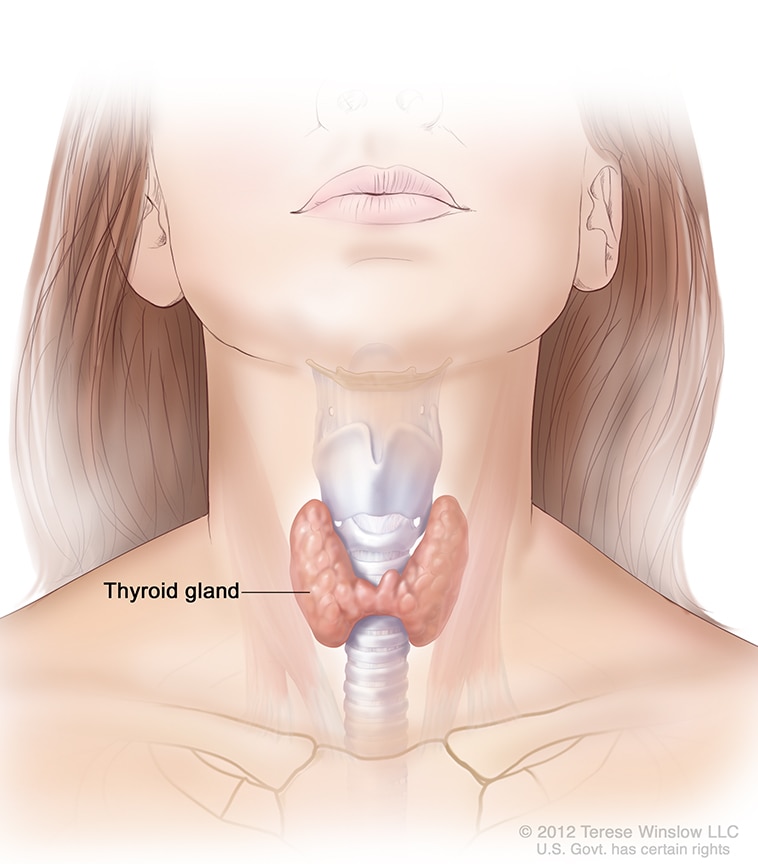

Hashimoto’s disease is an autoimmune disorder that can cause hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid. Rarely, the disease can cause hyperthyroidism, or overactive thyroid.

The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of your neck. In people with Hashimoto’s disease

- the immune system makes antibodies that attack the thyroid gland

- large numbers of white blood cells, which are part of the immune system, build up in the thyroid

- the thyroid becomes damaged and can’t make enough thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormones control how your body uses energy, so they affect nearly every organ in your body—even the way your heart beats.

The thyroid is a small gland in your neck that makes thyroid hormones.

The thyroid is a small gland in your neck that makes thyroid hormones.Does Hashimoto’s disease have another name?

Hashimoto’s disease is also called Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, or autoimmune thyroiditis.

How common is Hashimoto’s disease?

The number of people who have Hashimoto’s disease in the United States is unknown. However, the disease is the most common cause of hypothyroidism, which affects about 5 in 100 Americans.1

Who is more likely to have Hashimoto’s disease?

Hashimoto’s disease is 4 to 10 times more common in women than men.2 Although the disease may occur in teens or young women, it more often develops in women ages 30 to 50.3 Your chance of developing Hashimoto’s disease increases if other family members have the disease.

You are more likely to develop Hashimoto’s disease if you have other autoimmune disorders, including4

- celiac disease, a digestive disorder that damages the small intestine

- lupus, a chronic, or long-term, disorder that can affect many parts of the body

- rheumatoid arthritis, a disorder that affects the joints

- Sjögren’s syndrome, a disease that causes dry eyes and mouth

- type 1 diabetes, a disease that occurs when your blood glucose, also called blood sugar, is too high

What are the complications of Hashimoto’s disease?

Many people with Hashimoto’s disease develop hypothyroidism. Untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to several health problems, including5

- high cholesterol

- heart disease and heart failure

- high blood pressure

- myxedema, a rare condition in which the body’s functions slow down to the point that it can threaten your life

Left untreated, hypothyroidism can also cause problems during pregnancy.

What are the symptoms of Hashimoto’s disease?

Many people with Hashimoto’s disease have no symptoms at first. As the disease progresses, you may have one or more of the symptoms of hypothyroidism.

Some common symptoms of hypothyroidism include

- fatigue

- weight gain

- trouble tolerating cold

- joint and muscle pain

- constipation

- dry skin or dry, thinning hair

- heavy or irregular menstrual periods or fertility problems

- slowed heart rate

Hashimoto’s disease causes your thyroid to become damaged. Most people with Hashimoto’s disease develop hypothyroidism. Rarely, early in the course of the disease, thyroid damage may lead to the release of too much thyroid hormone into your blood, causing symptoms of hyperthyroidism.3

Your thyroid may get larger and cause the front of the neck to look swollen. The enlarged thyroid, called a goiter, may create a feeling of fullness in your throat, though it is usually not painful. After many years, or even decades, damage to the thyroid may cause the gland to shrink and the goiter to disappear.

A health professional examines a woman's neck.

A health professional examines a woman's neck.

What causes Hashimoto’s disease?

Researchers don’t know why some people develop Hashimoto’s disease, but a family history of thyroid disease is common. Several factors may play a role, including2

- genes

- viruses, such as hepatitis C

Hypothyroidism can also be caused by

- some medicines used to treat bipolar disorder or other mental health problems

- iodine-containing medicines used to treat abnormal heart rhythm

- exposure to toxins, such as nuclear radiation

How do doctors diagnose Hashimoto’s disease?

Doctors diagnose Hashimoto’s disease based on

- medical history and physical exam. Your doctor will start by taking a medical history and performing a physical exam. In addition to asking about symptoms, the doctor will check your neck for a goiter, which some people with Hashimoto’s disease can develop.

- blood tests. Your doctor will order one or more blood tests to check for hypothyroidism and its causes. Examples include tests for

- the thyroid hormones T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine)

- thyroid-stimulating hormone, or TSH

- thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO), a type of thyroid antibody that is present in most people with Hashimoto’s disease

You probably won’t need other tests to confirm you have Hashimoto’s disease. However, if your doctor suspects Hashimoto’s disease but you don’t have antithyroid antibodies in your blood, you may have an ultrasound of your thyroid. The ultrasound images can show the size of your thyroid and other features of Hashimoto’s disease. The ultrasound also can rule out other causes of an enlarged thyroid, such as thyroid nodules—small lumps in the thyroid gland.

How do doctors treat Hashimoto’s disease?

How your doctors treat Hashimoto’s disease usually depends on whether the thyroid is damaged enough to cause hypothyroidism. If you don’t have hypothyroidism, your doctor may choose to simply check your symptoms and thyroid hormone levels regularly.

You will take levothyroxine to replace the hormone your thyroid no longer makes.

You will take levothyroxine to replace the hormone your thyroid no longer makes.The medicine levothyroxine, which is identical to the natural thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4), is the recommended way to treat hypothyroidism. Prescribed in pill form for many years, this medicine is now also available as a liquid and in a soft gel capsule.2 These newer formulas may be helpful to people with digestive problems that affect how the thyroid hormone pill is absorbed.

Some foods and supplements can affect how well your body absorbs levothyroxine. Examples include grapefruit juice, espresso coffee, soy, and multivitamins that contain iron or calcium.1,6 Taking the medicine on an empty stomach can prevent this from happening. Your doctor may ask you to take the levothyroxine in the morning, 30 to 60 minutes before you eat your first meal.

Your doctor will give you a blood test about 6 to 8 weeks after you begin taking the medicine and adjust your dose if needed. Each time you change your dose, you’ll have another blood test. Once you’ve reached a dose that’s working for you, your doctor will likely repeat the blood test in 6 months and then once a year.

Never stop taking your medicine or take a higher dose without talking with your doctor first. Taking too much thyroid hormone medicine can cause serious problems, such as atrial fibrillation or osteoporosis.5

Your hypothyroidism can be well-controlled with thyroid hormone medicine, as long as you take the medicine as instructed by your doctor and have regular follow-up blood tests.

How does eating, diet, and nutrition affect Hashimoto’s disease?

The thyroid uses iodine, a mineral in some foods, to make thyroid hormones. However, if you have Hashimoto’s disease or other types of autoimmune thyroid disorders, you may be sensitive to harmful side effects from iodine. Eating foods that have large amounts of iodine—such as kelp, dulse, or other kinds of seaweed, and certain iodine-rich medicines—may cause hypothyroidism or make it worse. Taking iodine supplements can have the same effect.

Talk with members of your health care team about

- what foods and beverages to limit or avoid

- whether you take iodine supplements

- any cough syrups you take that may contain iodine

However, if you are pregnant, you need to take enough iodine because the baby gets iodine from your diet. Too much iodine can cause problems as well, such as a goiter in the baby. If you are pregnant, talk with your doctor about how much iodine you need.

Researchers are looking at other ways in which diet and supplements—such as vitamin D and selenium—may affect Hashimoto’s disease.2 However, no specific guidance is currently available.3

Clinical Trials for Hashimoto’s Disease

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including endocrine diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for Hashimoto’s disease?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about Hashimoto’s disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for Hashimoto’s disease are looking for participants?

You can find clinical studies on Hashimoto’s disease at ClinicalTrials.gov. In addition to searching for federally funded studies, you can expand or narrow your search to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Leonard Wartofsky, M.D., M.A.C.P., MedStar Georgetown University Hospital